Max Wyman addresses the importance of the Arts in Canada

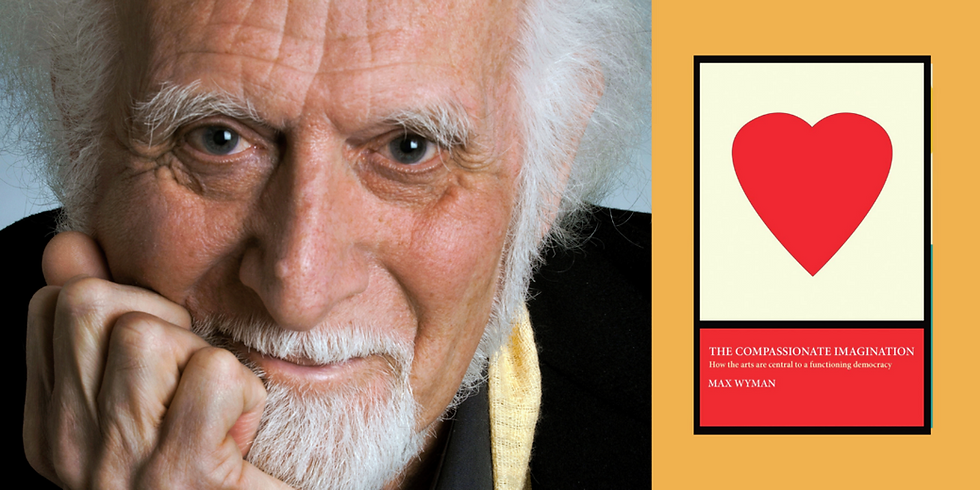

MAX WYMAN is a writer and for the past 30 years has been one of Canada’s leading cultural commentators, covering dance, music and drama for The Vancouver Sun and CBC Radio. He is the author of a number of books on the arts in Canada, and a former mayor of Lions Bay. The Watershed is delighted to share our interview with Wyman on the subject of his latest book, THE COMPASSIONATE IMAGINATION: How the arts are essential to a functioning democracy.

Watershed: In your new book, The Compassionate Imagination: How the Arts Are Central to a Functioning Democracy, you address the need for a radical reassessment of the role of art in today's society. Why is this so important? What do you mean by the phrase 'compassionate imagination'?

MW: I call this book The Compassionate Imagination because after more than fifty years watching Canadian creativity come into glorious flower, I am convinced that the arts and culture — in general, and in Canada specifically — have a unique power to reawaken our sense of decency and empathy toward one another and to regenerate a sense of common purpose in our increasingly splintered existence.

Our political leaders have historically had an uneasy relationship with the arts and culture. They make sure the sector gets resources sufficient for basic survival. But none of them have managed to grasp the need to stop seeing the arts sector as a frill, as an outlier, and to start engaging meaningfully with the arts and culture as a central and necessary element of our nationhood.

Typically, if you can’t value the outcome in dollars, it doesn’t count. Government values accountability. And it’s hard to show the value of art and culture on a cost-benefit graph. That means that those who spend their life advocating for the arts have been forced to try to prove their value in economic terms.

I’m here to totally reframe the argument. I’m proposing a new Canadian Cultural Contract that makes arts and culture integral to the lives of us all. Because if there ever was a time to take advantage of the transformational effect that art, culture and creativity can have on society, it’s now.

Watershed: Why is it important we make these changes now?

MW: Like it or not, we are at the end of the world as we knew it. The COVID-19 pandemic shook loose everything we thought was stable in society — health, work, community, family, friendship — and woke us all to the need for fundamental, systemic change. The systems under which we have operated are out of balance and close to toppling: the rich continue to get richer; the poor, poorer; the weather worse; and our countryside is burning at a faster rate than at any time in recorded history.

Too many factors make us feel we have nothing in common: social media, political differences, economic disparities, tribalism. Mutual trust has evaporated like the morning dew. We shout when we should be listening. But change on the scale the world needs now, in the manner we need now, won’t happen until we ratchet down the anger and the fear, dismantle the barriers between us, and find again that middle ground of generosity and shared humanity where we can come together to imagine a better, more inclusive, more humane society.

We need a vision of a world beyond the creeping normalization of greed and mistrust: a vision that is not only functional, something we are prepared to settle for, but inspirational, something to which we can aspire.

Sharing our imaginations through creative activity — letting our own imagination out to play for other people to share — lets us explore other people’s realities. It tells us that difference is not something to fear. It fosters fellow-feeling and engenders compassion. It puts us back in touch with the empathy, decency and care I believe we were born with.

But that’s not the only reason we need to bring the arts and culture to the centre of our lives together. Governments everywhere are floundering in the face of all these disruptions.

Watershed: What changes need to happen on a government level?

MW: As crisis piles on crisis we are ever more aware of the consequences of going the route of short-term political opportunism rather than the road where long-term ethical and moral choices prevail. Our traditional systems of governance, in which results are based on rationality and measurement aren’t up to the task of coping with the chaos and upheaval of the post-modern world.

They have to develop the flexibility—the nimbleness, the human relatedness—that takes uncertainty and complexity into full account. Imagination, ingenuity, and compassion are society’s rare earth metals, essential to prevent what even now threatens to be a slide back down society’s evolutionary ladder.

And it’s here that the creative sector—where outcomes are built on uncertainty and complexity and ambiguity—has useful contributions to make. Artists ask questions we might not voluntarily engage with. They upend old assumptions and encourage us to imagine alternatives and integrate moral sensibility into the answers we find.

My book lays out a solid framework for a new Canadian Cultural Contract between the government of Canada and the people it serves. It affirms art and culture as the humanizing core of Canadian civil society and an essential public service, and it embeds art’s unique and deeply human properties of imaginative exploration and emotional and spiritual enrichment d eep in public policy.

Watershed: Is this just a book for folks in the arts community? Who else do you think would enjoy or benefit from reading it?

MW: Frankly, it’s for everyone. Yes, the arts community certainly should read it, because it contains some fairly radical suggestions about how to change the way we fund cultural activity in Canada — and, come to that, some fairly radical suggestions about what should be included under that “cultural” umbrella.

But this isn’t the old familiar litany of neediness but a blueprint of opportunity—opportunity for a broad social transformation that reaches far beyond the concert hall and the art gallery and out into the places where we all live. It’s about harnessing an abundant natural resource that has been going to waste and putting it to work for the benefit of everyone.

I should add, by the way, that these ideas that I’ve been sketching for you aren’t just something plucked out of the ether by a wild-eyed, wild-haired prophet in the wilderness with too much time on his hands. The old system is broken—everywhere. Australia is currently having something of the same debate; so is the UK. We need something entirely different, adapted for modern times.

One of the most consistent responses I’ve been getting from early readers is that this book is something we have to get into the hands of our decision-makers —politicians at every level, educators, school boards, business leaders and the professional community. In fact, one Vancouver reader—a friend from many years—has already put up the funds to send a copy to every member of the federal cabinet. Other friends have bought it in bulk to distribute to their board colleagues.

Watershed: This is a big step away from the work you did in the Village when you were mayor. Can you address the significance of the arts on an absolutely local level? Why is it important for Lions Bay?

MW: They’re important at both the micro and the macro level.

Macro, it’s all about the integration of art and culture into public policy — as a teaching tool in the schools, changing STEM to STEAM and turning out more imaginative and flexible thinkers; as a healing tool in our physical and mental health systems; as an integral tool for healing in our public health systems; as a means to apply intuition and imagination to the baffling uncertainty that besets so many public policy decisions.

Micro, it’s about each of us getting involved with creative expression however we see fit.

But access to the arts and creative activity isn’t a level playing field in Canada, so one element of my proposed new Canadian Cultural Contract is a cultural credit, probably built into the tax and benefits structures, to enable every Canadian to do exactly that — to let loose the compassionate imagination, to feed the compassionate imagination, in ways of their own choosing.

Skeptics may scoff and call this kind of societal rethink pie-in-the-sky dreaming. We live in a time when many have thrown up their hands in despair at the way that greed and inequality and brazen lying have made a mockery of the social contract.

So this book draws the arc of the possible, not some fanciful ideal; it focuses on the pragmatic, well aware of the unpredictability and folly that lie at the heart of human nature. Our glorious cussedness. It offers no single solution, no magic wand that will overnight transform the world to a better place. It’s about looking at our cultural identity — what it constitutes and the way we express it — through a twenty-first century lens and thinking about how to make ourselves ready for where the rising tide of human concern and understanding will take us.

Thanks to Max Wyman for his insights on the arts in Canada today. If you have thoughts you'd like to share, please leave a comment below or email editor@lionsbaywatershed.ca

Commentaires